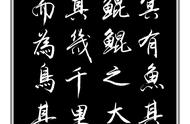

原文

北冥有鱼,其名为鲲。鲲之大,不知其几千里也。化而为鸟,其名为鹏。鹏 之背,不知其几千里也;怒而飞,其翼若垂天之云。是鸟也,海运则将徙于南冥。南冥者,天池也。

译文

北方的大海里有一条鱼,它的名字叫做鲲。鲲的体积,真不知道大到几十千里;变化成为鸟,它的名字就叫鹏。鹏的脊背,真不知道长到几千里;当它振翅而飞的时候,那展开的双翅就像天边的云。这只鹏鸟呀,随着海上汹涌的波涛迁徙到南方的大海。南方的大海是个天然的大池。

原文

《齐谐》者,志怪者也。《谐》之言曰:“鹏之徙于南冥也,水击三千里, 抟扶摇而上者九万里,去以六月息者也。”野马也,尘埃也,生物之以息相吹也。天之苍苍,其正色邪?其远而无所至极邪?其视下也,亦若是则已矣。

译文

《齐谐》是一部专门记载怪异事情的书,这本书上记载说:“鹏鸟迁徙到南方的大海,翅膀拍击水面激起三千里的波涛,乘着旋风环旋飞上几万里的高空,凭借着六月的大风才能离开”。春日林泽原野上蒸腾浮动犹如奔马的雾气,低空里沸沸扬扬的尘埃,都是大自然里各种生物的气息吹拂所致。天空是那么湛蓝的,难道这就是它真正的颜色吗?抑或是高旷辽远没法看到它的尽头呢?鹏鸟在高空往下看,不过也就像这个样子罢了。

原文

且夫水之积也不厚,则其负大舟也无力。覆杯水于坳堂之上,则芥为之舟;置杯焉则胶,水浅而舟大也。风之积也不厚,则其负大翼也无力。故九万里,则 风斯在下矣,而后乃今培风;背负青天而莫之夭阏者,而后乃今将图南。

译文

再说水汇积不深,它浮载大船就没有力量。倒杯水在庭堂的低洼处,那么小小的芥草也可以给它当做船;而搁置杯子就粘住不动了,因为水太浅而船太大了。风聚积的力量不雄厚,它托负巨大的翅膀便力量不够。所以,鹏鸟高飞九万里,狂风就在它的身下,然后方才凭借风力飞行,背负青天而没有什么力量能够阻遏它了,然后才像现在这样飞到南方去。

原文

蜩与学鸠笑之曰:“我决起而飞,抢榆枋,时则不至而控于地而已矣,奚以 之九万里而南为?”适莽苍者,三飡而反,腹犹果然;适百里者,宿舂粮;适 千里者,三月聚粮。之二虫又何知?

译文

寒蝉与斑鸠讥笑它说:“我从地面急速起飞,碰着榆树和檀树的树枝,常常飞不到而落在地上,为什么要到九万里的高空而向南飞呢?”到迷茫的郊野去,一日内可以往返,肚子还是饱饱的;到百里之外去,要用一整夜时间准备干粮;到千里之外去,三个月以前就要准备粮食。寒蝉和斑鸠这两个小东西懂得什么!

原文

小知不及大知,小年不及大年。奚以知其然也?朝菌不知晦朔,蟪蛄不知春 秋,此小年也。楚之南有冥灵者,以五百岁为春,五百岁为秋;上古有大椿者, 以八千岁为春,八千岁为秋。而彭祖乃今以久特闻,众人匹之,不亦悲乎!

译文

小聪明赶不上大智慧,寿命短比不上寿命长。怎么知道是这样的呢?清晨的菌类不会懂得什么是晦朔,寒蝉也不会懂得什么是春秋,这就是短寿。楚国南边有叫冥灵的大龟,它把五百年当做春,把五百年当做秋;上古有叫大椿的古树,它把八千年当做春,把八千年当作秋,这就是长寿。可是彭祖到如今还是以年寿长久而闻名于世,人们与他攀比,岂不可悲可叹吗?

原文

汤之问棘也是已。穷发之北有冥海者,天池也。有鱼焉,其广数千里,未有 知其修者,其名为鲲。有鸟焉,其名为鹏,背若太山,翼若垂天之云,抟扶摇羊 角而上者九万里,绝云气,负青天,然后图南,且适南冥也。

译文

商汤询问棘的话是这样的:“在那草木不生的北方,有一个很深的大海,那就是“天池”。那里有一种鱼,它的脊背有好几千里,没有人能够知道它有多长,它的名字叫做鲲,有一种鸟,它的名字叫鹏,它的脊背像座大山,展开双翅就像天边的云。鹏鸟奋起而飞,翅膀拍击急速旋转向上的气流直冲九万里高空,穿过云气,背负青天,这才向南飞去,打算飞到南方的大海。

原文

斥鷃笑之曰:“彼 且奚适也?我腾跃而上,不过数仞而下,翱翔蓬蒿之间,此亦飞之至也。而彼且 奚适也?”此小大之辩也。

译文

斥鴳讥笑它说:?它打算飞到哪儿去?我奋力跳起来往上飞,不过几丈高就落了下来,盘旋于蓬蒿丛中,这也是我飞翔的极限了。而它打算飞到什么地方去呢??”这就是小与大的不同了。

原文

故夫知效一官,行比一乡,德合一君,而徵一国者,其自视也亦若此矣。而 宋荣子犹然笑之。且举世而誉之而不加劝,举世而非之而不加沮,定乎内外之分, 辩乎荣辱之境,斯已矣。彼其于世未数数然也。虽然,犹有未树也。

译文

所以,那些才智足以胜任一个官职,品行合乎一乡人心愿,道德能使国君感到满意,能力足以取信一国之人的人,他们看待自己也像是这样哩。而宋荣子却讥笑他们。世上的人们都赞誉他,他不会因此越发努力,世上的人们都为难他,他也不会因此而更加沮丧。他清楚地划定自身与物外的区别,辩别荣誉与耻辱的界限,不过如此而已呀!宋荣子他对于整个社会,从来不急急忙忙地去追求什么。虽然如此,他还是未能达到最高的境界。

原文

夫列子御风而行,泠然善也,旬有五日而后反。彼于致福者,未数数然也。此虽免乎行,犹有所待者也。

译文

列子能驾风行走,那样子实在轻盈美好,而且十五天后方才返回。列子对于寻求幸福,从来没有急急忙忙的样子。他这样做虽然免除了行走的劳苦,可还是有所依凭呀。

原文

若夫乘天地之正,而御六气之辩,以游无穷者,彼 且恶乎待哉!故曰:至人无己,神人无功,圣人无名。

译文

至于遵循宇宙万物的规律,把握“六气”的变化,遨游于无穷无尽的境域,他还仰赖什么呢!因此说,道德修养高尚的“至人”能够达到忘我的境界,精神世界完全超脱物外的“神人”心目中没有功名和事业,思想修养臻于完美的“圣人”从不去追求名誉和地位。

原文

尧让天下于许由,曰:“日月出矣而爝火不息,其于光也,不亦难乎!时雨 降矣而犹浸灌,其于泽也,不亦劳乎!夫子立而天下治,而我犹尸之,吾自视缺 然。请致天下。”

译文

尧打算把天下让给许由,说:“太阳和月亮都已升起来了,可是小小的炬火还在燃烧不熄;它要跟太阳和月亮的光亮相比,不是很难吗?季雨及时降落了,可是还在不停地浇水灌地;如此费力的人工灌溉对于整个大地的润泽,不显得徒劳吗?先生如能居于国君之位天下一定会获得大治,可是我还空居其位;我自己越看越觉得能力不够,请允许我把天下交给你。”

原文

许由曰:“子治天下,天下既已治也。而我犹代子,吾将为名乎?名者,实 之宾也。吾将为宾乎?鹪鹩巢于深林,不过一枝;偃鼠饮河,不过满腹。归休乎 君,予无所用天下为!庖人虽不治庖,尸祝不越樽俎而代之矣。”

译文

许由回答说:“你治理天下,天下已经获得了大治,而我却还要去替代你,我将为了名声吗?“名”是“实”所派生出来的次要东西,我将去追求这次要的东西吗?鹪鹩在森林中筑巢,不过占用一棵树枝;鼹鼠到大河边饮水,不过喝满肚子。你还是打消念头回去吧,天下对于我来说没有什么用处啊!厨师即使不下厨,祭祀主持人也不会越俎代庖的!”

原文

肩吾问于连叔曰:“吾闻言于接舆,大而无当,往而不反。吾惊怖其言,犹 河汉而无极也;大有迳庭,不近人情焉。”连叔曰:“其言谓何哉?”曰:“藐姑射之山,有神人居焉,肌肤若冰雪,淖约若处子。不食五谷,吸风饮露,乘云 气,御飞龙,而游乎四海之外。其神凝,使物不疵疠而年谷熟。吾以是狂而不信 也。”连叔曰:“然。瞽者无以与乎文章之观,聋者无以与乎钟鼓之声。岂唯形 骸有聋盲哉?夫知亦有之。是其言也,犹时女也。之人也,之德也,将旁礴万物 以为一。世蕲乎乱,孰弊弊焉以天下为事!之人也,物莫之伤,大浸稽天而不溺, 大旱金石流土山焦而不热。是其尘垢秕糠,将犹陶铸尧舜者也,孰肯以物为事!”

译文

肩吾向连叔求教:“我从接舆那里听到谈话,大话连篇没有边际,一说下去就回不到原来的话题上。我十分惊恐他的言谈,就好像天上的银河没有边际,跟一般人的言谈差异甚远,确实是太不近情理了。”连叔问:“他说的是些什么呢?”肩吾转述道:“在遥远的姑射山上,住着一位神人,皮肤润白像冰雪,体态柔美如处女,不食五谷,吸清风饮甘露,乘云气驾飞龙,遨游于四海之外。他的神情那么专注,使得世间万物不受病害,年年五谷丰登。我认为这全是虚妄之言,一点也不可信。”连叔听后说:“是呀!对于瞎子没法同他们欣赏花纹和色彩,对于聋子没法同他们聆听钟鼓的乐声。难道只是形骸上有聋与瞎吗?思想上也有聋和瞎啊!这话似乎就是说你肩吾的呀。那位神人,他的德行,与万事万物混同一起,以此求得整个天下的治理,谁还会忙忙碌碌把管理天下当成回事!那样的人呀,外物没有什么能伤害他,滔天的大水不能淹没他,天下大旱使金石熔化、土山焦裂,他也不感到灼热。他所留下的尘埃以及瘪谷糠麸之类的废物,也可造就出尧舜那样的圣贤人君来,他怎么会把忙着管理万物当作己任呢!”

原文

宋人资章甫而适诸越,越人断发文身,无所用之。

译文

北方的宋国有人贩卖帽子到南方的越国,越国人不蓄头发满身刺着花纹,没什么地方用得着帽子。

原文

尧治天下之民,平海内之 政,往见四子藐姑射之山,汾水之阳,窅然丧其天下焉。

译文

尧治理好天下的百姓,安定了海内的政局,到姑射山上、汾水北面,去拜见四位得道的高士,不禁怅然若失,忘记了自己居于治理天下的地位。

原文

惠子谓庄子曰:“魏王贻我大瓠之种,我树之成而实五石。以盛水浆,其坚不能自举也。剖之以为瓢,则瓠落无所容。非不呺然大也,我为其无用而掊之。” 庄子曰:“夫子固拙于用大矣。宋人有善为不龟手之药者,世世以洴澼絖为事。客闻之,请买其方百金。聚族而谋曰:“我世世为洴澼絖,不过数金;今一朝而鬻技百金,请与之。”客得之,以说吴王。越有难,吴王使之将,冬与 越人水战,大败越人,裂地而封之。能不龟手,一也;或以封,或不免于洴澼 絖,则所用之异也。今子有五石之瓠,何不虑以为大樽而浮乎江湖,而忧其瓠 落无所容?则夫子犹有蓬之心也夫!”

译文

惠子对庄子说:“魏王送我大葫芦种子,我将它培植起来后,结出的果实有五石容积。用大葫芦去盛水浆,可是它的坚固程度承受不了水的压力。把它剖开做瓢也太大了,没有什么地方可以放得下。这个葫芦不是不大呀,我因为它没有什么用处而砸烂了它。”庄子说:“先生实在是不善于使用大东西啊!宋国有一善于调制不皲手药物的人家,世世代代以漂洗丝絮为职业。有个游客听说了这件事,愿意用百金的高价收买他的药方。全家人聚集在一起商量:?我们世世代代在河水里漂洗丝絮,所得不过数金,如今一下子就可卖得百金。还是把药方卖给他吧。?游客得到药方,来游说吴王。正巧越国发难,吴王派他统率部队,冬天跟越军在水上交战,大败越军,吴王划割土地封赏他。能使手不皲裂,药方是同样的,有的人用它来获得封赏,有的人却只能靠它在水中漂洗丝絮,这是使用的方法不同。如今你有五石容积的大葫芦,怎么不考虑用它来制成腰舟,而浮游于江湖之上,却担忧葫芦太大无处可容?看来先生你还是心窍不通啊!”

原文

惠子谓庄子曰:“吾有大树,人谓之樗。其大本拥肿而不中绳墨,其小枝卷 曲而不中规矩。立之途,匠者不顾。今子之言,大而无用,众所同去也。”庄子 曰:“子独不见狸狌乎?卑身而伏,以候敖者;东西跳梁,不辟高下;中于机 辟,死于罔罟。今夫斄牛,其大若垂天之云。此能为大矣,而不能执鼠。今子有 大树,患其无用,何不树之于无何有之乡,广莫之野,彷徨乎无为其侧,逍遥乎 寝卧其下。不夭斤斧,物无害者,无所可用,安所困苦哉!”

译文

惠子又对庄子说:“我有棵大树,人们都叫它“樗”。它的树干却疙里疙瘩,不符合绳墨取直的要求,它的树枝弯弯扭扭,也不适应圆规和角尺取材的需要。虽然生长在道路旁,木匠连看也不看。现今你的言谈,大而无用,大家都会鄙弃它的。”庄子说:“先生你没看见过野猫和黄鼠狼吗?低着身子匍伏于地,等待那些出洞觅食或游乐的小动物。一会儿东,一会儿西,跳来跳去,一会儿高,一会儿低,上下窜越,不曾想到落入猎人设下的机关,死于猎网之中。再有那斄牛,庞大的身体就像天边的云;它的本事可大了,不过不能捕捉老鼠。如今你有这么大一棵树,却担忧它没有什么用处,怎么不把它栽种在什么也没有生长的地方,栽种在无边无际的旷野里,悠然自得地徘徊于树旁,优游自在地躺卧于树下。大树不会遭到刀斧砍伐,也没有什么东西会去伤害它。虽然没有派上什么用场,可是哪里又会有什么困苦呢?”

《庄子·逍遥游》英译本

版本1:

A Happy Excursion

In the northern ocean there is a fish, called the k‘un, I do not know how many thousand li in size. This k‘un changes into a bird, called the p‘eng. Its back is I do not know how many thousand li in breadth. When it is moved, it flies, its wings obscuring the sky like clouds.

When on a voyage, this bird prepares to start for the Southern Ocean, the Celestial Lake. And in the Records of Marvels we read that when the p‘eng flies southwards, the water is smitten for a space of three thousand li around, while the bird itself mounts upon a great wind to a height of ninety thousand li, for a flight of six months‘duration.

There mounting aloft, the bird saw the moving white mists of spring, the dust-clouds, and the living things blowing their breaths among them. It wondered whether the blue of the sky was its real color, or only the result of distance without end, and saw that the things on earth appeared the same to it.

If there is not sufficient depth, water will not float large ships. Upset a cupful into a hole in the yard, and a mustard-seed will be your boat. Try to float the cup, and it will be grounded, due to the disproportion between water and vessel.

So with air. If there is not sufficient a depth, it cannot support large wings. And for this bird, a depth of ninety thousand li is necessary to bear it up. Then, gliding upon the wind, with nothing save the clear sky above, and no obstacles in the way, it starts upon its journey to the south.

A cicada and a young dove laughed, saying, "Now, when I fly with all my might, ‘tis as much as I can do to get from tree to tree. And sometimes I do not reach, but fall to the ground midway. What then can be the use of going up ninety thousand li to start for the south?"

He who goes to the countryside taking three meals with him comes back with his stomach as full as when he started. But he who travels a hundred li must take ground rice enough for an overnight stay. And he who travels a thousand li must supply himself with provisions for three months. Those two little creatures, what should they know?

Small knowledge has not the compass of great knowledge any more than a short year has the length of a long year. How can we tell that this is so? The fungus plant of a morning knows not the alternation of day and night. The cicada knows not the alternation of spring and autumn. Theirs are short years. But in the south of Ch‘u there is a mingling (tree) whose spring and autumn are each of five hundred years‘duration. And in former days there was a large tree which had a spring and autumn each of eight thousand years. Yet, P‘eng Tsu is known for reaching a great age and is still, alas! an object of envy to all!

It was on this very subject that the Emperor T‘ang spoke to Chi, as follows: "At the north of Ch‘iungta, there is a Dark Sea, the Celestial Lake. In it there is a fish several thousand li in breadth, and I know not how many in length. It is called the k‘un. There is also a bird, called the p‘eng, with a back like Mount T‘ai, and wings like clouds across the sky. It soars up upon a whirlwind to a height of ninety thousand li, far above the region of the clouds, with only the clear sky above it. And then it directs its flight towards the Southern Ocean.

"And a lake sparrow laughed, and said: Pray, what may that creature be going to do? I rise but a few yards in the air and settle down again, after flying around among the reeds. That is as much as any one would want to fly. Now, wherever can this creature be going to?" Such, indeed, is the difference between small and great.

Take, for instance, a man who creditably fills some small office, or whose influence spreads over a village, or whose character pleases a certain prince. His opinion of himself will be much the same as that lake sparrow‘s. The philosopher Yung of Sung would laugh at such a one. If the whole world flattered him, he would not be affected thereby, nor if the whole world blamed him would he be dissuaded from what he was doing. For Yung can distinguish between essence and superficialities, and understand what is true honor and shame. Such men are rare in their generation. But even he has not established himself.

Now Liehtse could ride upon the wind. Sailing happily in the cool breeze, he would go on for fifteen days before his return. Among mortals who attain happiness, such a man is rare. Yet although Liehtse could dispense with walking, he would still have to depend upon something.

As for one who is charioted upon the eternal fitness of Heaven and Earth, driving before him the changing elements as his team to roam through the realms of the Infinite, upon what, then, would such a one have need to depend? Thus it is said, "The perfect man ignores self; the divine man ignores achievement; the true Sage ignores reputation."

The Emperor Yao wished to abdicate in favor of Hsu: Yu, saying, "If, when the sun and moon are shining, the torch is still lighted, would it be not difficult for the latter to shine? If, when the rain has fallen, one should still continue to water the fields, would this not be a waste of labor? Now if you would assume the reins of government, the empire would be well governed, and yet I am filling this office. I am conscious of my own deficiencies, and I beg to offer you the Empire."

"You are ruling the Empire, and the Empire is already well ruled," replied Hsu: Yu. "Why should I take your place? Should I do this for the sake of a name? A name is but the shadow of reality, and should I trouble myself about the shadow? The tit, building its nest in the mighty forest, occupies but a single twig. The beaver slakes its thirst from the river, but drinks enough only to fill its belly. I would rather go back: I have no use for the empire! If the cook is unable to prepare the funeral sacrifices, the representative of the worshipped spirit and the officer of prayer may not step over the wines and meats and do it for him."

Chien Wu said to Lien Shu, "I heard Chieh Yu: talk on high and fine subjects endlessly. I was greatly startled at what he said, for his words seemed interminable as the Milky Way, but they are quite detached from our common human experience."

"What was it?" asked Lien Shu.

"He declared," replied Chien Wu, "that on the Miao-ku-yi mountain there lives a divine one, whose skin is white like ice or snow, whose grace and elegance are like those of a virgin, who eats no grain, but lives on air and dew, and who, riding on clouds with flying dragons for his team, roams beyond the limit‘s of the mortal regions. When his spirit gravitates, he can ward off corruption from all things, and bring good crops. That is why I call it nonsense, and do not believe it."

"Well," answered Lien Shu, "you don‘t ask a blind man‘s opinion of beautiful designs, nor do you invite a deaf man to a concert. And blindness and deafness are not physical only. There is blindness and deafness of the mind. His words are like the unspoiled virgin. The good influence of such a man with such a character fills all creation. Yet because a paltry generation cries for reform, you would have him busy himself about the details of an empire!

"Objective existences cannot harm. In a flood which reached the sky, he would not be drowned. In a drought, though metals ran liquid and mountains were scorched up, he would not be hot. Out of his very dust and siftings you might fashion two such men as Yao and Shun. And you would have him occupy himself with objectives!"

A man of the Sung State carried some ceremonial caps to the Yu:eh tribes for sale. But the men of Yu:eh used to cut off their hair and paint their bodies, so that they had no use for such things.

The Emperor Yao ruled all under heaven and governed the affairs of the entire country. After he paid a visit to the four sages of the Miao-ku-yi Mountain, he felt on his return to his capital at Fenyang that the empire existed for him no more.

Hueitse said to Chuangtse, "The Prince of Wei gave me a seed of a large-sized kind of gourd. I planted it, and it bore a fruit as big as a five bushel measure. Now had I used this for holding liquids, it would have been too heavy to lift; and had I cut it in half for ladles, the ladles would have been too flat for such purpose. Certainly it was a huge thing, but I had no use for it and so broke it up."

"It was rather you did not know how to use large things," replied Chuangtse. "There was a man of Sung who had a recipe for salve for chapped hands, his family having been silk-washers for generations. A stranger who had heard of it came and offered him a hundred ounces of silver for this recipe; whereupon he called together his clansmen and said, ‘We have never made much money by silk-washing. Now, we can sell the recipe for a hundred ounces in a single day. Let the stranger have it.‘

"The stranger got the recipe, and went and had an interview with the Prince of Wu. The Yu:eh State was in trouble, and the Prince of Wu sent a general to fight a naval battle with Yu:eh at the beginning of winter. The latter was totally defeated, and the stranger was rewarded with a piece of the King‘s territory. Thus, while the efficacy of the salve to cure chapped hands was in both cases the same, its applications were different. Here, it secured a title; there, the people remained silk-washers.

"Now as to your five-bushel gourd, why did you not make a float of it, and float about over river and lake? And you complain of its being too flat for holding things! I fear your mind is stuffy inside."

Hueitse said to Chuangtse, "I have a large tree, called the ailanthus. Its trunk is so irregular and knotty that it cannot be measured out for planks; while its branches are so twisted that they cannot be cut out into discs or squares. It stands by the roadside, but no carpenter will look at it. Your words are like that tree -- big and useless, of no concern to the world."

"Have you never seen a wild cat," rejoined Chuangtse, "crouching down in wait for its prey? Right and left and high and low, it springs about, until it gets caught in a trap or dies in a snare. On the other hand, there is the yak with its great huge body. It is big enough in all conscience, but it cannot catch mice. Now if you have a big tree and are at a loss what to do with it, why not plant it in the Village of Nowhere, in the great wilds, where you might loiter idly by its side, and lie down in blissful repose beneath its shade? There it would be safe from the axe and from all other injury. For being of no use to others, what could worry its mind?"

版本2:

Free and Easy Wandering

In the northern darkness there is a fish and his name is K‘un. The K‘un is so huge I don‘t know how many thousand li he measures. He changes and becomes a bird whose name is P‘eng. The back of the P‘eng measures I don‘t know how many thousand li across and, when he rises up and flies off, his wings are like clouds all over the sky. When the sea begins to move, this bird sets off for the southern darkness, which is the Lake of Heaven.

The Universal Harmony records various wonders, and it says: “When the P‘eng journeys to the southern darkness, the waters are roiled for three thousand li. He beats the whirlwind and rises ninety thousand li, setting off on the sixth-month gale.”Wavering heat, bits of dust, living things blown about by the wind - the sky looks very blue. Is that its real color, or is it because it is so far away and has no end? When the bird looks down, all he sees is blue too.

If water is not piled up deep enough, it won‘t have the strength to bear up a big boat. Pour a cup of water into a hollow in the floor and bits of trash will sail on it like boats. But set the cup there and it will stick fast, for the water is too shallow and the boat too large. If wind is not piled up deep enough, it won‘t have the strength to bear up great wings. Therefore when the P‘eng rises ninety thousand li, he must have the wind under him like that. Only then can he mount on the back of the wind, shoulder the blue sky, and nothing can hinder or block him. Only then can he set his eyes to the south.

The cicada and the little dove laugh at this saying, ``When we make an effort and fly up, we can get as far as the elm or the sapanwood tree, but sometimes we don‘t make it and just fall down on the ground. Now how is anyone going to go ninety thousand li to the south!‘‘

If you go off to the green woods nearby, you can take along food for three meals and come back with your stomach as full as ever. If you are going a hundred li, you must grind your grain the night before; and if you are going a thousand li you must start getting together provisions three months in advance. What do these two creatures understand? Little understanding cannot come up to great understanding; the short-lived cannot come up to the long-lived.

How do I know this is so? The morning mushroom knows nothing of twilight and dawn; the summer cicada knows nothing of spring and autumn. They are short-lived. South of Ch‘u there is a caterpillar which counts five hundred years as one spring and five hundred years as one autumn. Long, long ago there was a great rose of Sharon that counted eight thousand years as one spring and eight thousand years as one autumn. Yet P‘eng-tsu alone is famous today for having lived a long time, and everybody tries to ape him. Isn‘t it pitiful!

Among the questions of T‘ang to Ch‘i we find the same thing. In the bald and barren north, there is a dark sea, the Lake of Heaven. In it is a fish which is several thousand li across, and no one knows how long. His name is K‘un. there is also a bird there, named P‘eng, with a back like Mount T‘ai and wings like clouds filling the sky. He beats the whirlwind, leaps into the air, and rises up ninety thousand li, cutting through the clouds and mist, shouldering the blue sky, and then he turns his eyes south and prepares to journey to the southern darkness.

The little quail laughs at him, saying, ``Where does he think he‘s going? I give a great leap and fly up, but I never get more than ten or twelve yards before I come down fluttering among the weeds and brambles. And that‘s the best kind of flying anyway! Where does he think he‘s going?‘‘Such is the difference between big and little.

Therefore a man who has wisdom enough to fill one office effectively, good conduct enough to impress one community, virtue enough to please one ruler, or talent enough to be called into service in one state, has the same kind of self-pride as these little creatures. Sung Jung-tzu would certainly burst out laughing at such a man. The whole world could praise Sung Jung-tzu and it wouldn‘t make him exert himself; the whole world could condemn him and it wouldn‘t make him mope. He drew a clear line between the internal and the external, and recognized the boundaries of true glory and disgrace. But that was all. As far as the world went, he didn‘t fret or worry, but there was still ground he left unturned.

Lieh Tzu could ride the wind and go soaring around with cool and breezy skill, but after fifteen days he came back to earth. As far as the search for good fortune went, he didn‘t fret and worry. He escaped the trouble of walking, but he still had to depend on something to get around. If he had only mounted on the truth of Heaven and Earth, ridden the changes of the six breaths, and thus wandered through the boundless, then what would he have had to depend on?

Therefore I say, the Perfect Man has no self; the Holy Man has no merit; the Sage has no fame.